Fisherwomen advocate for sustainable seafood practices at Waterfront talks

Pictured in front is fisherwoman Michelle Singh, from Hout Bay, and asking a question is fisherwoman Rovina Europa.

Image: Fouzia Van Der Fort

In a powerful discussion, local fisherwomen challenge chefs and restaurateurs on sustainable seafood practices, advocating for their communities and the future of fishing.

They questioned them on the meaning of sustainability; whether local fishing communities were included in collecting data, learning and employment opportunities for their youth; and how they could collate a partnership across professions and industries.

On Thursday June 19, non-profit organisation (NPO) V&A Waterfront SOLVE hosted the panel discussion and had guests, fisherwomen, from Abalobi (meaning fisher in isiXhosa) language; and the University of the Western Cape’s Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS) at Maker’s Landing.

Pictured from left are panelists chefs Chris Erasmus, Gregory Henderson, Veronica Canha-Hibbert, Abalobi director of growth Chris Kastern, World Wide Fund South Africa (WWF SA) corporate engagement and behaviour change lead Pavs (Pavitray) Pillay, chef Grethel Ferreira, and moderator Two Oceans Aquarium Foundation’s executive of strategic projects Dr Judy Mann.

Image: Fouzia Van Der Fort

SOLVE was launched in March 2021 as part of the Waterfront’s commitment to using the structural break provided by Covid-19 to build back better.

They aim to provide focus for the Waterfront, to engage with the challenges in the realms of sustainability, opportunity and inclusivity.

The South African fishing NPO strives to promote small-scale fisheries for ecological, economic and social sustainability.

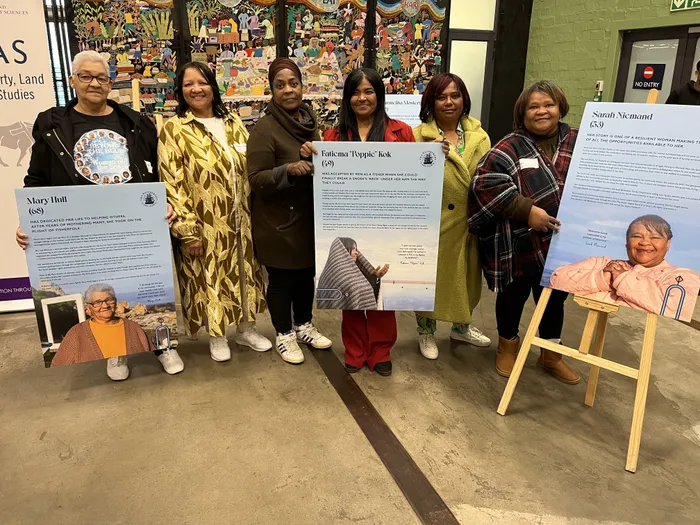

Fisherwomen Mary Hull, from Kleinmond, Charmaine Daniels, from Ocean View, Michelle Singh, from Hout Bay, Fatiema Kok, from Ocean View, Rovina Europa, from Arniston, and Sarah Niemand, from Buffelsjagsbaai, some for them were featured in a book published by the University of the Western Cape’s Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS).

Image: Fouzia Van Der Fort

Moderator, Two Oceans Aquarium Foundation’s executive of strategic projects, Dr Judy Man,n directed discussions to address five key ways to overcome these barriers and restore fisheries to health and sustainability:

- Serving only seasonal seafood.

- Telling stories about the seafood on the menu – and the species omitted from it.

- Educating chefs and waiting staff about sustainable seafood.

- Procuring responsibly by insisting on supply chain transparency and traceability; forging partnerships between restaurants and organisations such as Abalobi

- Seasonality

Following this discussion, the fisherwomen posed their questions and shared their lived experiences.

Fisherwoman Michelle Singh, from Hout Bay, asked how the restaurant industry was making fishing viable for her as an indigenous fisher.

“Went to sea. Born and bred in the sea. Still busy in the sea and in the harbour in Hout Bay. How do you really work with local communities and local fishers? What do you really call sustainability if I know that some of our products come via the sea, go to other countries, and then come back to our country?” she asked.

Ms Singh said that most of the poaching was being done by deep-sea trawlers.

She invited the panellists to visit her at the harbour to see how fishing communities sustain themselves.

“We can take care of our seas ourselves. Come see how we do it. How we sustain ourselves. We use a fish from the tail, up into the intestines and in the head. A full snoek, hake and kingklip,” she said.

Fisherwoman Rovina Europa, from Arniston, asked whether the government was WWF SA‘s main source of information for statistics on endangered species.

“This is also a very big challenge for our community. We have youth who are born fishers that matriculated. Got no training. No jobs, no opportunities. How about that partnership? Because it is all about learning and earning. You need to learn first before you can earn something,” she said.

Ms Europa said the best way to collect data was from the fishers.

“What they experience day by day. And that's where you can make your decisions. Because the challenge we have in our communities for sustainability is the fish we eat daily, or the neighbours in our community, who use the line fish. A lot of them are limited. Tuna is a really healthy fish. From the government, you need a permit for the volume of fish you are allowed to catch. The market determines the volume of fish you are allowed to catch,” she said.

NGO World Wide Fund launched the Southern African Sustainable Seafood Initiative (SASSI) 21 years ago, to help consumers, restaurants, and retailers make informed choices about seafood; to promote sustainable fishing practices and protect marine ecosystems.

The initiative uses a "traffic light" system (red, orange and green) to categorise fish species based on their sustainability, guiding consumers towards more responsible seafood choices.

Panellist WWF SA (South Africa) corporate engagement and behaviour change lead Pavs (Pavitray) Pillay, said they were seeing more species on the red list than before.

“We are seeing the bigger, more resilient species that can handle the fishing pressure, like hake and stuff on the green list, and they’ve been there for a while,” she said.

She said that much of the fish caught by small-scale fishers were not being documented or used in the bigger markets.

“There are multiple people exploiting those species and these biological species are not productive to maximum amounts to be taken out.

“Most of our line fish species aggregate and they spawn. They should not be taken out of the water because they haven’t yet laid their eggs. Those are the kind of things we are trying,” she said.

Ms Pillay said that most of their data informing their SASSI assessments came from the government.

“We speak to the fishing industry, we are trying to, and we’re slowly trying to get data from small-scale fishers, but as you know, small-scale fishers have been marginalised for years and years. In terms of getting their data has been difficult. We have been working with Abalobi, who have been collecting the data from their different communities, and hopefully we can use that data to start using it in some of those species that are critical for the small communities,” she said.

Commi chef students from Cape Peninsula University of Technology Lwazi Msibi, from Mountainhouse residence, Iviwe Tikayo, from Langa, and Anita Mshumpela, from Parklands, add some finishing touches.

Image: Fouzia Van Der Fort

Ms Pillay said that WWF has been working for about 17 years with small-scale fishers and has trained about 70 youth who are now employed through the Stony Point penguin colony. “We’ve got youth that are running our bait and underwater remote camera tracks, and they’re collecting the data for us, so we can see what’s in Betty's Bay MPA (Marine Protected Area).

“We’ve got two or three of them working for Cape Nature. So we are trying to work with this. “The indigenous knowledge is difficult to gather. We need to find mechanisms where we can gather that data and we can use it in the assessments,” she said.

Ms Pillay said that for the first time, last year, when the SASSI methodology was updated, they added five questions around indigenous knowledge, local data, human dimensions and even around climate change, which affects the oceans.

“We’re trying,” she said.

Sassi is an ecological rating system based on what is happening in the water.

It is informed by data from the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (DFFE).

“I agree with you, there are lots of issues with that data from DFFE, but we also use data that is in the public realm that is being published by scientists that is being collected by different organisations, including places like Abalobi,” she said.

Ms Pillay also explained that bycatch was the bane of everyone’s existence, not just the small fishers.

“In South Africa, we have it slightly better, in that some of our trawl industry by-catch does have a bit of a quota. So kingklip is a by-catch, monkfish is a by-catch, yet they’re targeting hake,” she said.

She said that by-catch, dead or dying, was tossed overboard.

“By-catch is not just consumable fish. People forget by-catch is sharks, turtles, seabirds, so there are lots of issues with by-catch, and that’s somewhere we need regulators and regulatory authorities to step up and start dealing with it,” she said.

Ms Pillay said that the NGO could not close down a restaurant, but that the DFFE could.

“They’re selling a red-listed species. DFFE needs to do that and when it's an illegal species. DFFE needs to step up and do better with compliance and monitoring, you know, and we have to work with them to get that capacity up as well,” she said.

Veronica Canha-Hibbert, executive chef at The Silo Hotel at the Waterfront, said chefs would benefit from more education about sustainable seafood.

“When I grew up, it was hake, kingklip and snoek,” she said.

“I’ve learned a lot since then, but chefs need to know what is out there, what’s available.

“Learning about new fish and learning how to treat them will also enable us to learn different

cooking methods and styles. We work with Abalobi, and it broadened my knowledge, so I think we should acknowledge that we need to learn more and then have SASSI and Abalobi teach us.”

She said that it was also important to educate the waiting staff.

“It’s the waiters who explain to guests what the fish of the day is. If they get excited about these fish, then we sit with the luxury of being able to create a demand by making it fashionable. And doing exciting things with a very simple product will make people a bit more interested in it,” said Ms Canha-Hibbert.

V&A Waterfront retail food lead and curator Allister Esau and V&A Waterfront SOLVE director Heather Parker.

Image: Fouzia Van Der Fort

Heather Parker, the director of SOLVE, said the discussion had shown that sustainable fisheries which meet the needs of ecosystems, communities, chefs and diners were possible, but achieving them was not straightforward.

She said that the NGO was there to share the value ecosystem into practice, which means pioneering innovative solutions and supporting anyone who wants to learn from experience.

“We’re delighted that restaurants and hotels at the Waterfront are so engaged with the

challenges of sustainable seafood. The partnerships we’ve forged are bearing fruit, and we look forward to sharing the lessons we’ve learnt more widely in the hospitality sector,” said Ms Parker.

Chefs and students from across the peninsula.

Image: Fouzia Van Der Fort